"Condition of 'Our' Condition"

"If you don't know where you are going, any road will get you there." ~ Lewis Carroll ~

economist.com

American finance, always unique, is now uniquely dangerous

The Economist

May 29th 2025

A LWAYS A HAVEN in dangerous times, America has itself become a source of instability. The list of anxieties is long. Government debt is rising at an alarming pace. Trade policy is beset by legal conflicts and uncertainties. Donald Trump is attacking the country’s institutions. Foreign investors are skittish and the dollar has tumbled. Yet, astonishingly, one big danger lurks unnoticed still.

When you think of financial risk, you may picture investment-banking capers on Wall Street or subprime mortgages in Miami. But, as our special report explains, over the past decade American finance has been transformed. A mix of asset managers, hedge funds, private-equity firms and trading firms—including Apollo, BlackRock, Blackstone, Citadel, Jane Street, KKR and Millennium—have emerged from the shadows to elbow aside the incumbents. They are fundamentally different from the banks, insurers and old-style funds they have replaced. They are also big, complex and untested.

The financial revolution is now encountering the MAGA revolution. Mr Trump is hastening the next financial crisis by playing havoc with trade, upending America’s global commitments and, most of all, by prolonging the government’s borrowing binge. America’s financial system has long been dominant, but the world has never been as exposed to it. Everyone should worry about its fragility.

The new firms are a magnet for financial talent. They also enjoy regulatory advantages, because governments forced banks to hold more capital and rein in their traders after the financial crisis of 2007-09. That combination has led to a spate of innovation, supercharging the firms’ growth and propelling them into every corner of finance.

Three big private-markets firms, Apollo, Blackstone and KKR, have amassed $2.6trn in assets, almost five times as much as a decade ago. In that time the assets of large banks grew by just 50% to $14trn. In the search for stable funding, the upstarts have turned to insurance; Apollo, which made its name in private equity and merged with its insurance arm in 2022, now issues more annuities than any other American insurer. The firms lend to households and blue-chip companies such as Intel. Apollo alone lent $200bn last year. Loans held by large banks increased by just $120bn. New-look trading firms dominate stockpicking and marketmaking. In 2024 Jane Street earned as much trading revenue as Morgan Stanley.

There is much to like about this new financial system. It has been highly profitable. In some ways, it is also safer. Banks are vulnerable to runs because depositors fear being the last in the queue to withdraw their money. All things being equal, finance is more stable when loans are financed by money that is locked up for longer periods.

Most importantly, the dynamism of American finance has channelled capital towards productive uses and world-beating ideas, fuelling its economic and technological outperformance. The artificial-intelligence boom is propelled by venture capital and a new market for data-centre-backed securities. Bank-based financial systems in Europe and Asia cannot match America’s ability to mobilise capital. That has not only set back those regions’ industries, it has also drawn money into America. Over the past decade, the stock of American securities owned by foreigners doubled, to $30trn.

Unfortunately, the new finance also contains risks. And they are poorly understood. Indeed, because they are novel and untested by a crisis, they have never been quantified.

One lot of worries come from within the system. The new giants are still bank-like in surprising ways. Although it is costly to redeem a life-insurance policy early, a run is still possible should policy holders and other lenders fear that the alternative is to get back nothing. And although the banks are safer, depositors are still exposed to the new firms’ risk-taking. Bank loans to non-bank financial outfits have doubled since 2020, to $1.3trn. Likewise, the leverage supplied to hedge funds by banks has ballooned from $1.4trn in 2020 to $2.4trn today.

The new system is also dauntingly opaque. Whereas listed assets are priced almost in real time, private assets are highly illiquid. Mispriced risks can be masked until assets are suddenly revalued, forcing end investors to scramble to cover their losses. Novel financial techniques have repeatedly blown up in the past because financial innovators are driven to test their inventions to breaking-point and, the first time round, that threshold is unknown.

Under Mr Trump, the next upheaval is never far away. The government’s excessive borrowing imperils bond markets, alarming foreign investors. Although a court has this week limited the president’s powers to wage trade wars, the administration is appealing and Mr Trump is unlikely to abandon tariffs altogether. A toxic combination of uncertainty, institutional conflict, volatile asset prices, higher capital costs and economic weakness threatens to put the new-look financial system under almighty strain.

A crisis would test even the most capable policymaker. Much about the risks of the superstar firms, and their linkages to the wider financial system and the real economy, will become clear only when trouble strikes. New emergency-lending schemes would be needed. Rescuing banks last time was politically toxic. Saving billionaire investors would be an altogether harder task. And yet if the biggest of these giant firms were left to fail, it could lead to a global credit crunch.

Under Mr Trump a rescue would be unpredictable. In 2008 the Treasury and the Federal Reserve acted quickly to save the banks, and set up swap lines to offer dollar funding to much of the world. Mr Trump might decide to bail out everyone. But imagine the panic if he started to pick his favourite financiers, threatened to abandon or charge countries that displeased him and changed his mind every five minutes on Truth Social.

There will be another financial crisis—there always is. Nobody knows when disaster will strike. But when it does, investors will suddenly wake up to the fact that they are dealing with a financial system they do not recognise. ■

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference." ~ Reinhold Niebuhr

ft.com

Donald Trump’s fiscal policy and Fed attacks imperil US haven status, say economists

Eva Xiao, Claire Jones

6,29,2025

Donald Trump’s “breathtaking fiscal policy excess” and attacks on the Federal Reserve’s independence risk diminishing the US’s status as the ultimate haven for foreign investors, economists polled by the Financial Times have warned.

The poll, conducted by the Kent A Clark Center for Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, found that more than 90 per cent of economists surveyed were either somewhat or very concerned about the haven role of US dollar-denominated assets over the next five to 10 years.

The White House insisted this week that Trump’s economic policies will help cut US debt as it made a final pitch to win over fiscal hawks in the Senate and get the president’s flagship tax bill over the line.

But independent estimates, including by fiscal watchdog the Congressional Budget Office, indicate the measures contained in the budget bill — which Trump has dubbed “the big beautiful bill” — will push the US federal debt past its previous post-second world war high later this decade.

While the dollar usually appreciates during bouts of global market panic, the sharp sell-off in global equity markets following Trump’s unveiling of aggressive reciprocal tariffs on April 2 was coupled with a depreciation of the US currency.

The benchmark S&P 500 has since recovered and is at an all-time high amid hopes that Trump’s economic policies will not derail growth or fuel inflation in the world’s largest economy.

“The safe-haven assets appear to be [the] Swiss Franc and gold. In fact, [the] US looks like an emerging market, whereby policy uncertainty leads to rising risk premia that drive long-term yields up and the currency value down,” said Saroj Bhattarai at the University of Texas at Austin.

The dollar is trading at a three-year low amid concerns over fiscal sustainability and question marks over the Federal Reserve’s independence, as Trump continues to attack chair Jay Powell over his reluctance to cut interest rates amid concerns that the global trade war could push up inflation.

“Breathtaking fiscal policy excess is all but guaranteed, and that invites, though hardly guarantees, a change of heart about dollar assets,” said Robert Barbera at Johns Hopkins University.

“Marry that emerging reality to a de facto White House takeover of the Fed — through a Powell firing or the championing of a hack as a Powell replacement? That would move me from somewhat concerned to very, very concerned.”

Powell’s term ends in May 2026 and speculation is rife that Trump could name his pick to replace him early in an attempt to undermine the Fed chair.

“Fiscal deficits, deliberate government actions to shrink the US financial account and devalue the dollar, uncertainty about succession at the Fed and questions about Fed independence all negatively affect [the safe haven status of the dollar],” said Anna Cieslak at Duke University.

US Treasury yields, which usually fall in times of market volatility, rose in early April. While the benchmark 10-year yield has since fallen to about 4.3 per cent, many economists polled believe it could soon hit 5 per cent — a level that would spark concern within the Trump administration.

Almost three-quarters of the survey’s 47 respondents tipped the yield on 10-year debt to rise above 5 per cent by the middle of next year.

“US Treasury [bonds] might not be a safe asset any more,” said Evi Pappa at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. “Look at what happened at ‘liberation day’ to the US 10-year versus European yields.”

Economists have become more gloomy on the US outlook since they were last polled in March.

The median expectation is now for the world’s largest economy to expand by 1.5 per cent over the course of this year, slightly down from an estimate of 1.6 per cent in the spring.

Separate surveys of economists and US households and businesses show that forecasts for growth and confidence sank rapidly after the April 2 tariffs were announced, but have since partially recovered on the back of the trade truce between the US and China and rises in equity prices.

Economists have also become more hawkish on price pressures, with the median expectations for core PCE inflation this year moving up from 2.8 per cent in March to 3 per cent in June, amid expectations that Trump’s tariffs would be passed on to US consumers.

But only a few respondents believed there was a more than 50 per cent chance of core PCE inflation exceeding 4 per cent and the unemployment rate simultaneously exceeding 5 per cent at any point between now and the end of 2026.

A better than expected reading for consumer price index inflation in May boosted hopes that less of the cost of tariffs than feared would be passed on to American shoppers.

But the annual figure for core personal consumption expenditures inflation in May, published on Friday, rose slightly to 2.7 per cent, from 2.6 per cent the previous month.

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

"Facts do not organize themselves into systematic knowledge, except from a point of view. This point of view amounts to a theory." ~ Gunnar Myrdal ~

~ What's Your 'Point Of View' ? ~

$$

jacobin.com

Financial Capitalism Is More Dangerous Than Ever Today

Matthias Schmelzer

06.29.2025

The crash of 2008 was supposed to augur the end of ultraspeculative financial capitalism. But financial actors have actually gone from strength to strength since then, and fictitious capital is a bigger menace to global economic stability than ever.

Signage for a Bitcoin ATM in Barcelona, Spain, on November 11, 2024. (Angel Garcia / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Our summer issue examines the role of speculation in contemporary capitalism. Click here to

This is an extract from Freedom for Capital, Not People: The Mont Pèlerin Society and the Origins of the Neoliberal Monetary Order, now available from Verso Books.

Some writers have taken the period since the crisis of financial capitalism in 2008 to mark the “end of neoliberalism” or the advent of “post-neoliberalism.” Others have described it as a “mutant,” “zombie” iteration of a neoliberalism that is in effect “half-dead, half-alive.”

In an era of rising protectionism, right-wing ideology, and deglobalization, neoliberal ideologies have certainly experienced a backlash. But they have also rearticulated themselves by forging new alliances and taking on novel forms. Three dimensions of the current conjuncture are worth highlighting.

The Politics of Money

Today, as in the 1960s, there is an immense interest in the form that money takes as a central factor in politics and social life. Monetary policy is more than ever a political question of direct concern to people otherwise uninterested in its arcana. There is reason to think that the global system of money and finance is approaching a disruptive threshold of historic significance, with the potential to change how societies invest, insure, and trade.

Of course, the form of money — essentially the socially and politically constructed “promise to pay” — has always fluctuated. What is distinctive about the transformation of money in the early-twenty-first century is, first of all, the proliferation of digital currencies and tokens. Operating in the shadows of hegemonic monetary systems, these cannot simply be seen as tools for bottom-up emancipation pitted against authoritarian central banks and austerity-inducing monetary politics, as is sometimes claimed by their boosters.

There is an immense interest in the form that money takes as a central factor in politics and social life.

Rather, non-fungible tokens, Web3, blockchain technology, crypto, and decentralized autonomous organizations are at the forefront of a financial revolution driven increasingly by transnational platforms and central banks themselves. In the name of flexibility and efficiency, they prefigure the end of physical cash, thereby jeopardizing privacy and further undermining democracy. Such developments signal the exhaustion of the quantitative easing (QE) regime since 2019.

Although they are far too complex to be analyzed in any detail here, they represent one prospectus for the so-called post-neoliberal order, whose features cannot be understood as progressive, promising in some instances to surrender still more authority to the lords of finance themselves, potentially directly by administrative means.

The terms in which this new monetary architecture is discussed recall earlier debates. In the field of digital currencies, for example, the highly restricted, limited, and market-disciplining logic of Bitcoin bears comparison to the built-in scarcity of gold — and if introduced more broadly, could reproduce the logic of the gold standard — while the seemingly endless proliferation of absurdly branded private money over the decade of QE resembles the wild speculation enabled by free-floating exchange rates.

To this familiar opposition, a third pole may be added: central bank digital currency, issued either formally by central banks themselves or — what is functionally equivalent — by the largest private banks. This novel form of money is distinct in that it introduces the prospect of directly imposing socio-political conditions on transactions or penalizing savers through very low interest rates.

It is perhaps for this reason that the more principled neoliberals themselves have joined in to sound the alarm when it comes to some of these innovations. As the historian Adam Tooze has suggested, paraphrasing Antonio Gramsci, “crypto is the morbid symptom of an interregnum, an interregnum in which the gold standard is dead but a fully political money that dares to speak its name has not yet been born.”

Exorbitant Privilege

Another live issue in contemporary discussions is the status of the dollar as the world reserve currency, an “exorbitant privilege” ratified by the shift to floating exchange rates. The effects of this fateful decision, as a volume published on its fiftieth anniversary records, “went far beyond the international monetary system and have had momentous geopolitical and political as well as economic and financial implications.”

Today, if dollar hegemony remains intact, ever more voices question its permanence, and with it, the ability of the United States to maintain its unrivaled geopolitical position. In this regard, the present moment echoes that of the 1970s, when monetary policy reflected the jostling between world powers and management of the relations among allies. With the introduction of the BRICS basket of currencies and the prospect of de-dollarization it suggests, in the aftermath of Brexit and the eurozone crisis, forecasts of re-regionalization often turn on monetary policy.

If dollar hegemony remains intact, ever more voices question its permanence, and with it, the ability of the US to maintain its unrivaled geopolitical position.

Still, amid chatter of deglobalization and evidence of a fall in capital flows, the share of transactions conducted in dollars has remained relatively stable over the last decades. Nonetheless, the US “dollar creditocracy” is threatened by the internal contradictions of QE, and the US current account and budget deficits continue to exert downward pressure on the dollar, exacerbating resentment of US unilateralism.

Finally, the liberalization of capital movements in the 1970s must be seen as one side of the exhaustion of economic growth across the advanced industrialized countries; both are effects of overaccumulation and declining productivity growth and have taken the form of secular stagnation. The subsequent period has seen a tremendous explosion of fictitious capital, or financial assets that are in essence claims on future production and profit.

The financialization of the post-Fordist era has produced a lopsided economy, where such claims exceed by significant measure the size of the underlying real economy. Its logic is that of a growthless casino, based on transfer and appropriation largely decoupled from real-world use values. Such a top-heavy dynamic was exactly what produced the over-leveraging responsible for the 2008 meltdown.

Fictitious Capital

Pledges to reregulate and curb the power of finance aside, the metastasis of fictitious capital has continued apace. While the use of some assets — those complex instruments at the heart of the housing and financial crisis, such as CDOs — did indeed decline, the overall quantity of fictitious capital has in fact continued to increase. This dynamic is evinced by the outsize importance of the finance, insurance, and real estate (FIRE) sector and the run-up in prices of housing and art objects as financialized assets.

Trading in global foreign exchange markets — the marketplace that determines the exchange rate for global currencies and that originates in its modern form from abolishing the Bretton Woods system — soared from negligible levels in the 1970s to a nominal value of $620 billion in 1989 and $4.5 trillion in 2008; by 2022 it stood at $7.5 trillion. Such massive flows of money, buoying what some have called a “technofeudal” rentier class, pose a potentially systemic problem given the attendant pressure to seek their realization in the real economy.

In the age of climate overshoot, secular stagnation, and polycrisis, these claims on future production — now far greater than global GDP — create a fundamental dilemma. Given mounting evidence that calls into question the ambition of greening economic growth, efforts to realize future profits of fictitious capital will lead to either unsustainable growth that dangerously destabilizes planetary life or an alternative post-growth scenario, in which societies regain democratic control and turn fictitious capital into stranded assets.

Contributors

Matthias Schmelzer is a professor of social-ecological transformation at the University of Flensburg and director of the Norbert Elias Center for Transformation Design & Research. He is the author of The Hegemony of Growth: The OECD and the Making of the Growth Paradigm.

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

"Never argue with stupid people, they will drag you down to their level and then beat you with experience." ~ Mark Twain ~

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

~TajMo ~

"Room On The Porch"

$$

economist.com

Financial giants are transforming Wall Street

Thomas Bennett hails their innovation and dynamism, but warns against hubris

The Economist

May 23rd 2025

Finance is an industry moulded by disaster. It took a civil war to bring America’s banks under federal supervision, a banking panic to create the Federal Reserve and a Great Depression for the government to insure deposits. Yet the reformist urge that burns hot in the moment of catastrophe has a tendency to fade. Lessons are forgotten, innovations happen and regulations become regarded as a nuisance. New risks emerge—as do new titans, who defend their successor system vigorously and convincingly. The conclusion of one crisis begins the countdown to the next.

Wall Street has never failed as spectacularly as it did in 2008. Its executives fuelled a dramatic increase in borrowing which helped inflate a housing bubble. The complexity of its financial instruments had made the system’s fragility invisible even to insiders. After the subprime-mortgage market faltered, liquidity vanished across the financial system. Lehman Brothers was one of hundreds of banks to fail. Had the state not bailed out the biggest lenders, things would have got much worse. Reform crystallised in measures such as the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010, which subjected banks to a vast compliance bureaucracy. Lenders have been forced to hold more capital and to rein in their traders.

Regulators can choose whom to target but have less control over the firms that succeed in their place. In 2008 Charles Goodhart, an economist, described the “boundary problem” in finance. Setting and policing the boundary between regulated and unregulated institutions is hard, he argued, partly because risk-takers inevitably respond to regulation by shifting their activities into areas that are watched less closely.

Chart: The Economist

That is exactly what happened. Since the crisis, and especially in the past few years, a handful of American asset managers have thrived, often in areas that were the province of banks. Their lending activities, often called private credit, have grown rapidly, in part because banks are hemmed in by regulators. Hedge funds dominate trading activities where banks once held sway. Loose monetary policy helped. So did voracious global demand for American assets—these firms are beneficiaries of American exceptionalism.

Executives at these firms believe their success confirms the wisdom of the new financial order (see chart). The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, which recklessly borrowed from uninsured depositors who then ran for the exit in 2023, confirmed their view of banks as poorly run and intrinsically vulnerable.

But is a reckoning coming? How would loans made by private-credit funds perform in a recession? How risky is the growth in borrowing by hedge funds? Versions of these questions are being asked in every major financial institution and central bank.

Donald Trump’s chaotic presidency is making these questions more urgent. On April 2nd Mr Trump “liberated” America’s economy by announcing massive and arbitrary tariffs. Financial markets promptly went on a vertiginous ride, their volatility reaching levels surpassed only in 2008, at the height of the financial crisis, and in March 2020, at the beginning of the pandemic. Stocks had their fifth-worst two-day decline since the second world war. Companies’ cost of capital soared. Confidence among consumers and executives has been badly shaken.

Chart: The Economist

The self-inflicted trade crisis at times looked like it might precipitate a full-on financial crisis. Yields on America’s government debt surged while the value of the dollar plummeted, suggesting investors were fleeing American assets despite higher returns—a troubling dynamic typically reserved for emerging markets in turmoil, not the global financial hegemon.

Calm, or its semblance, has returned. Some executives see a real-world “stress test” completed—or even defeated, given how quickly Mr Trump bent to markets and paused the full implementation of his tariffs. Share prices in the big private-markets asset managers are still down a quarter of their value since their post-election peak in November, but markets have stabilised. Some contend only the pride of the Wall Street bosses who supported Mr Trump has been damaged.

Pride goeth before a fall

But to be sanguine is to be naive. Even if Mr Trump manages to refrain from smashing up global trade, the contrast between America’s fine-tuned financial system and the chaotic condition of its politics is too stark to ignore. Wall Street thrives on the rule of law and globalisation, both things which Mr Trump spurns. Many of the conditions of a financial meltdown are in place. The national debt sits at $36trn, close to a record relative to the size of the economy. Asset prices are inflated—and could easily be deflated if foreign investors decided to sell.

As this special report shows, financial innovation has transformed Wall Street. As in eras past, surging asset values have concealed cracks in the new financial order. Whatever dangers are lurking, Mr Trump’s presidency will make them more dangerous still. ■

$$$

"A person who won't read has no advantage over one who can't read"

~ Mark Twain ~

$

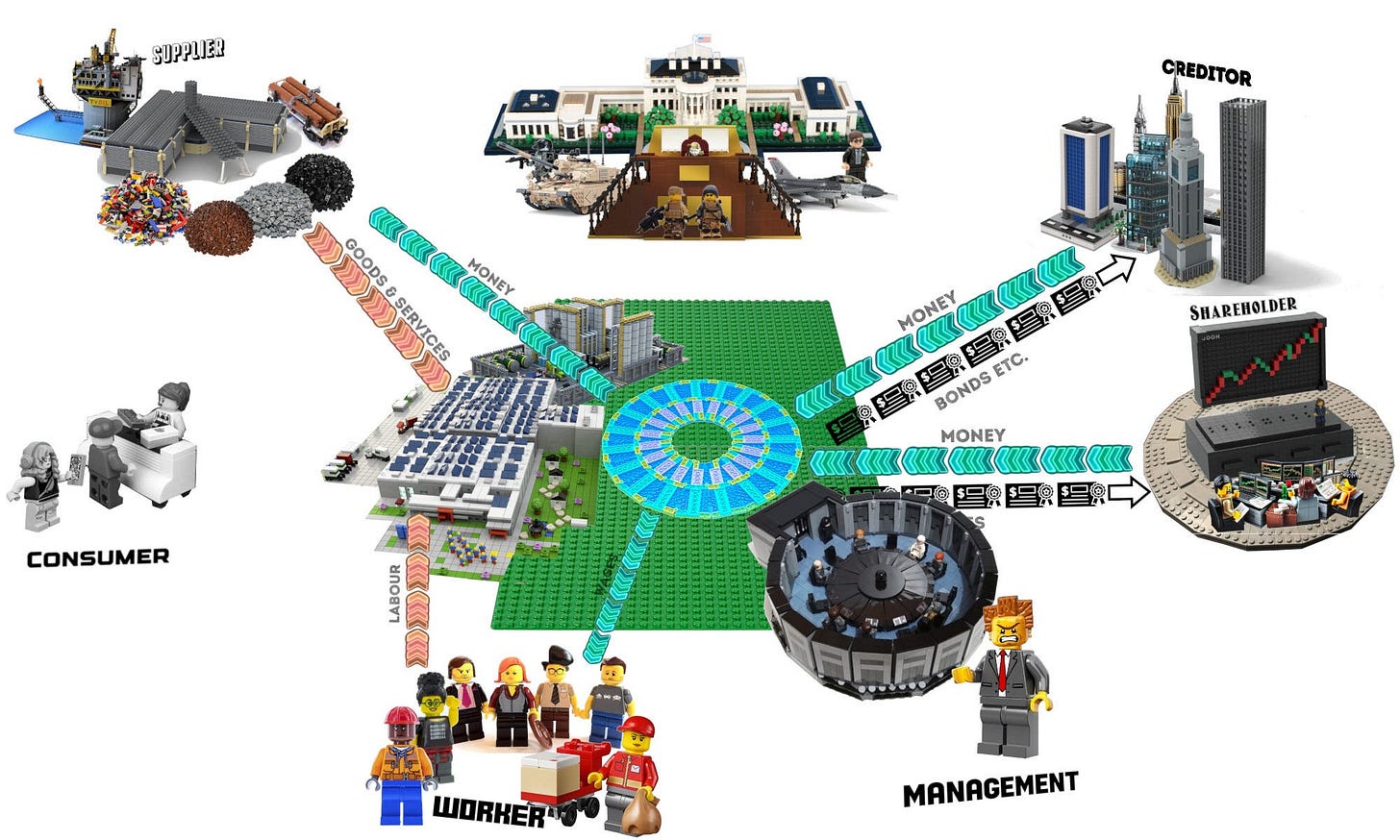

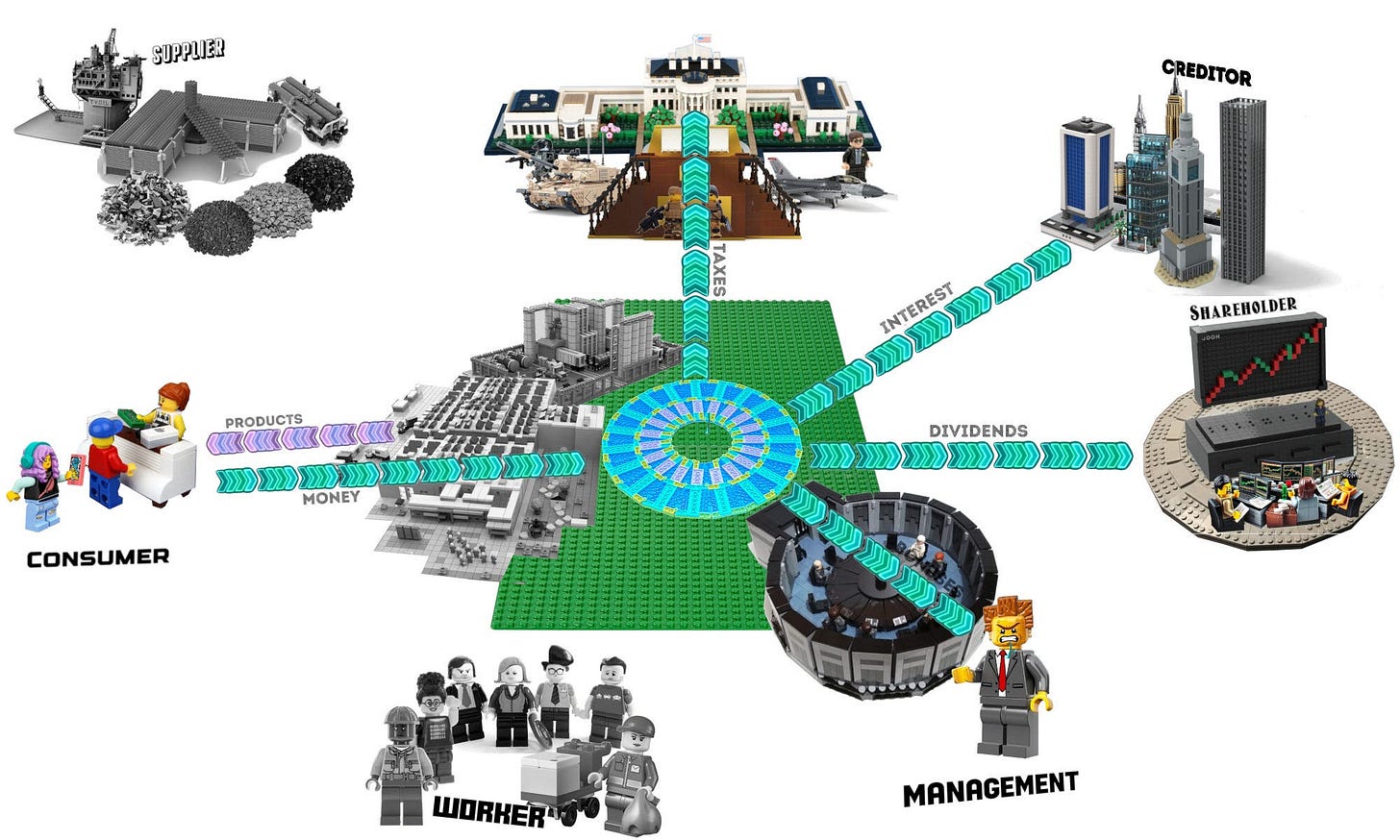

Lego Capitalism

A Lego Model of Financial Capitalism

Unboxing the dark arts of finance

Brett Scott

Apr 04, 2024

Dear readers: this piece builds upon my Lego Model of Corporate Capitalism

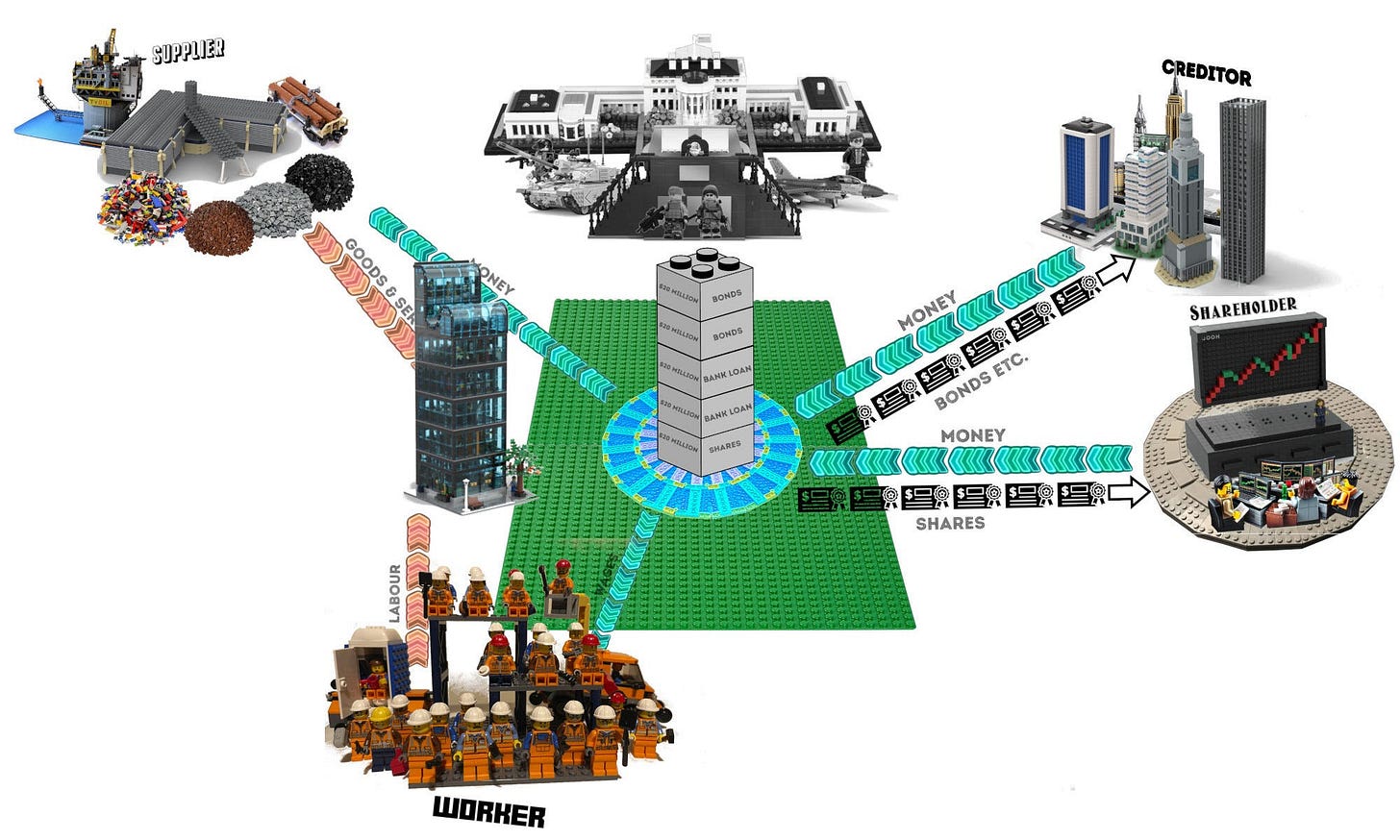

Our economies are held together by money, and - most of the time - we hand it over in exchange for goods or labour. Occasionally, however, we hand it over in exchange for future money. For example, if you buy a share on the stock-market, you’re handing over money for a contract promising you a cut of the future profits of a company.

This type of exchange, in which we exchange money for promises-for-future-money, is called financial exchange, and the financial markets are where it happens. Like many markets, the financial markets have a retail side - the smaller players like you and me - and a wholesale side, the mega players like funds, commercial banks and investment banks. The latter players cluster in big cities like London, New York, Singapore and Hong Kong, and in A Lego Model of Corporate Capitalism I showed them taking the lead on capitalizing international corporations. They ‘charge up’ corporate entities with money in exchange for financial contracts like shares and bonds, after which the corporates can blast that out to mobilize workers and suppliers to produce stuff…

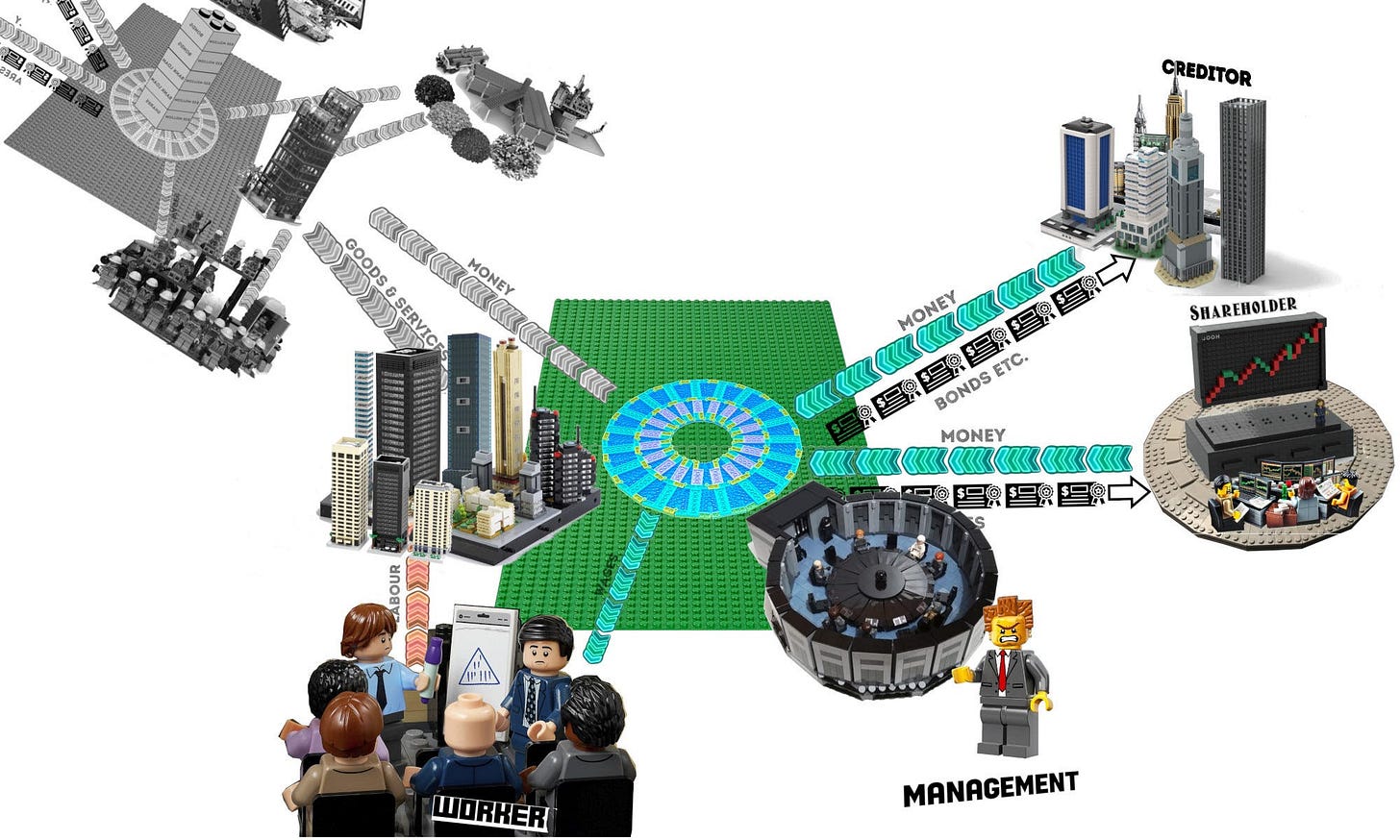

That stuff is then is sold to customers, and the revenues are refracted out as bonuses to management, interest to creditors, taxes to governments and dividends to shareholders.

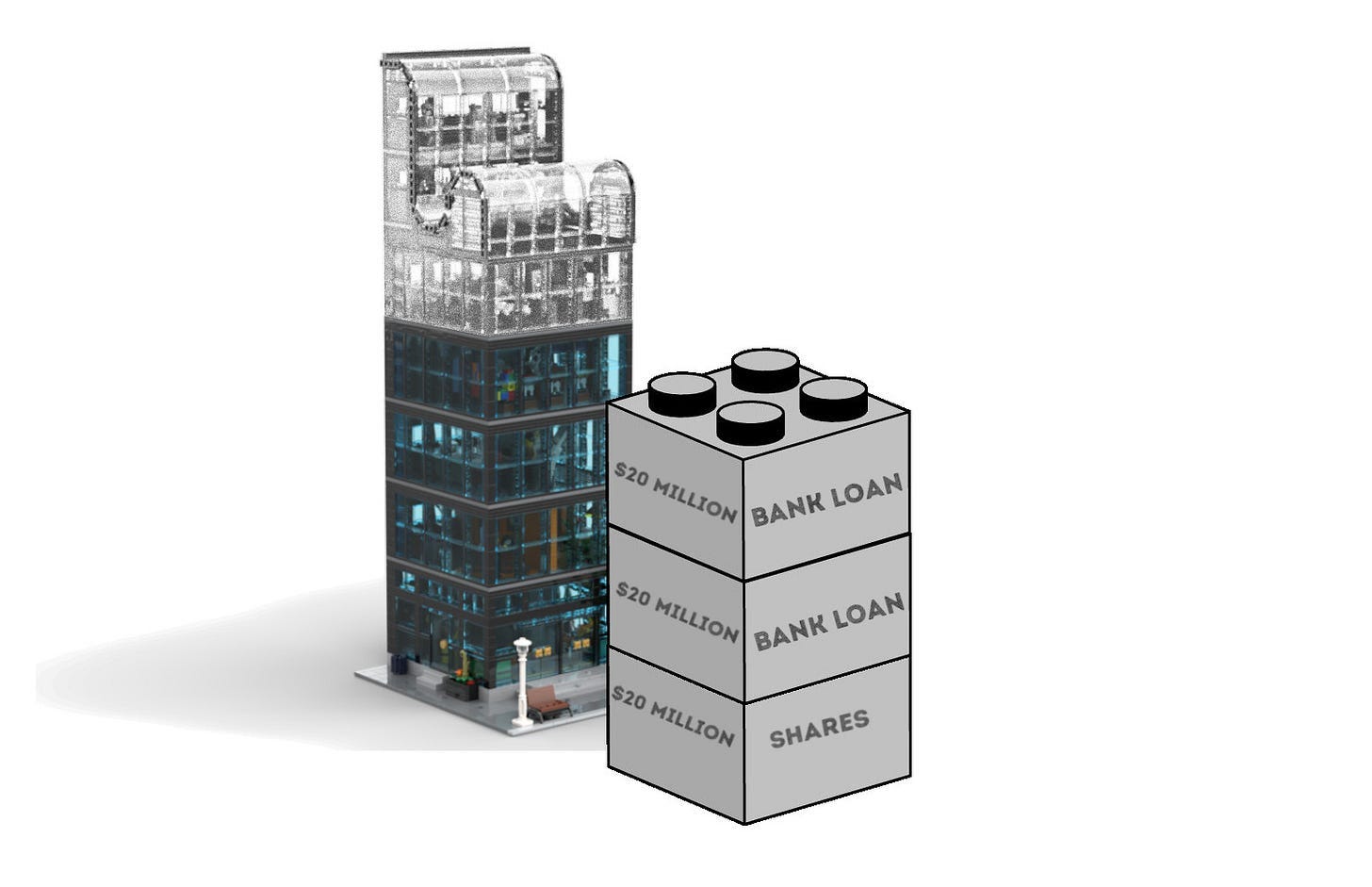

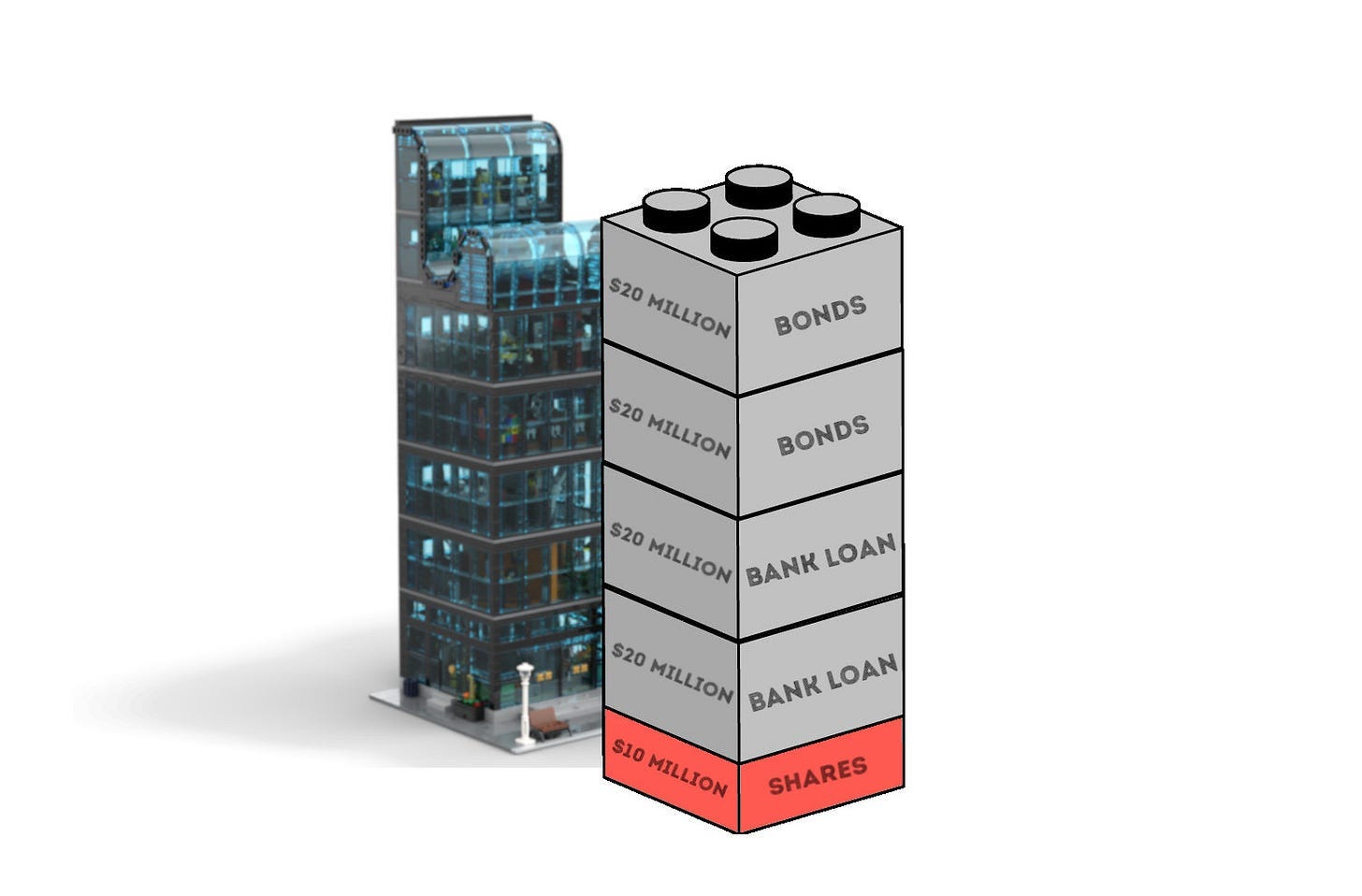

Building a Lego balance sheet

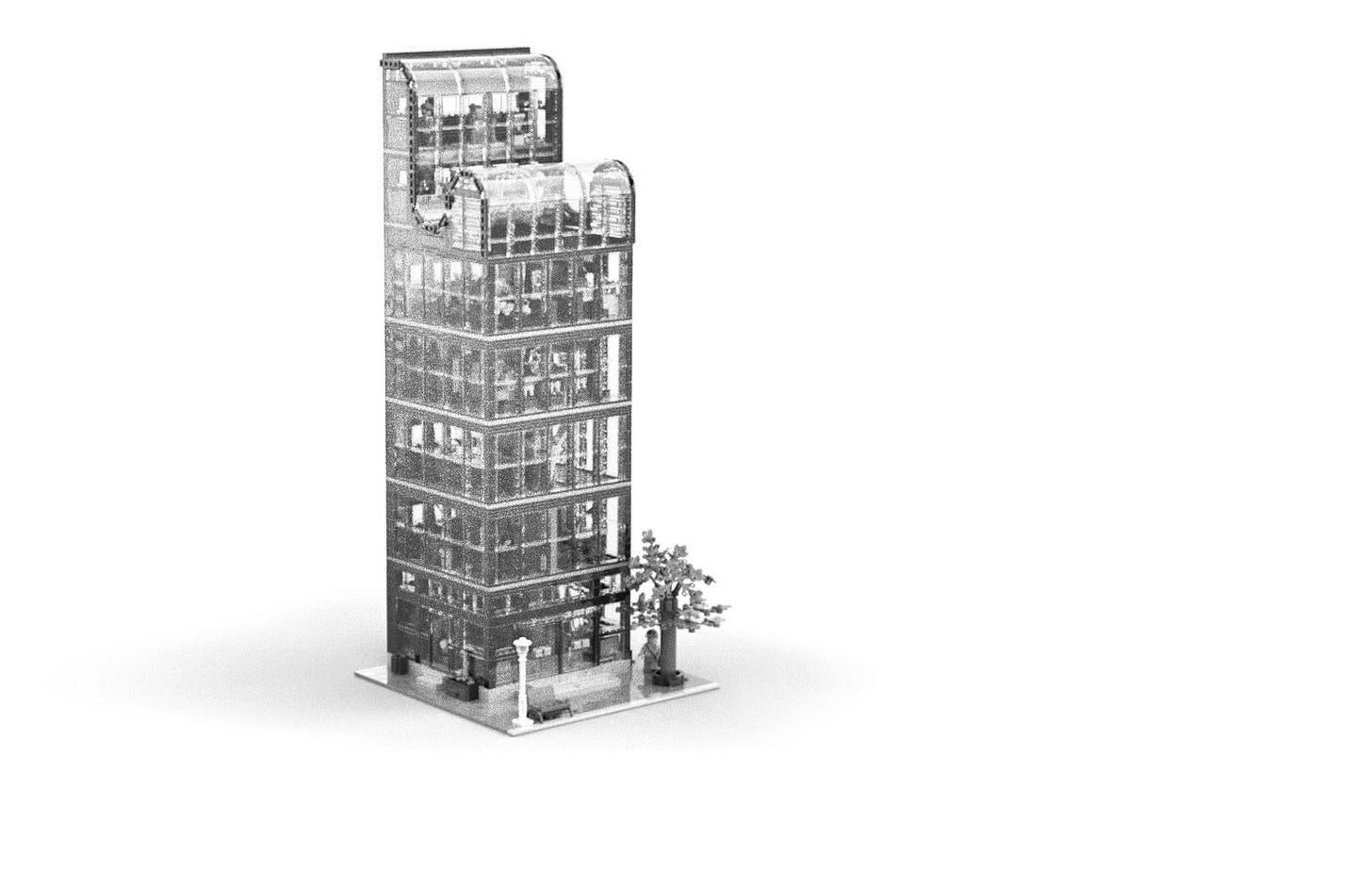

The company shown above is some kind of industrial corporation, but let’s start from scratch in a different sector. Let’s say you’re actually a wealthy property developer who wants to build a luxury office complex for startups in down-town Manhattan. You envision a 6-storey building with open-plan workspaces, a meditation den, a fitness spa, and even sound-proofed booths for therapeutic screaming when the existential emptiness of yuppie life kicks in. Here’s the vision:

Above I said ‘you want to build’, but that’s just a colloquial figure of speech. It’s not like you’re going to turn up with a spade and trowel to lay foundations for this building. No, what you actually want is for a thousand builders with specialist skills, equipment and materials to turn this vision into a reality. You nevertheless want to claim ownership of what they build, so to make sure they have no ownership rights, you need to approach them as suppliers selling goods and services in the open markets. That’s going to cost you about $100 million.

The way to obtain that money is through financial exchange: you need investors to give it to you in exchange for promises-for-future-money. Investment banks are specialists in convincing big investors to do this, but this is a small-ish project and you don’t want a massive investment bank like Goldman Sachs. Instead, you want a small boutique investment bank. You find one called BlueGate Partners. On their website they describe themselves as follows:

That phrase ‘debt and equity capital’ is finance slang for creditors and shareholders who will put in money for different promises-for-future-money. ‘Equity investors’ are shareholders: they put in money in exchange for shares of ownership that will entitle them to a morphing stream of future money (dividends). ‘Debt investors’ are creditors: they put in money in exchange for a promise for an fixed amount of future money (interest and principle). The promise given to equity investors is relative - the returns depend on how well things turn out - while the promise given to creditors is absolute - the amounts remains the same regardless of circumstances. From a legal perspective, absolute promises tend to be senior: they get dealt with first if everything goes to shit (which becomes particularly important in bankruptcy proceedings).

ASOMOCO is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Equity and debt investors will jointly capitalize projects or companies alongside each other. That said, the specific balance of power between them - and between the relative and absolute promises they’ve extracted - can create some interesting properties. One of these is leverage, the phenomenon by which debt investors amplify the returns of equity investors in exchange for protection (equity investors agree to absorb the first losses in a project, but also get to claim amplified gains). Leverage increases as the ratio between debt investors and equity investors increases, so the first thing you and BlueGate will work on is the optimal mix of equity and debt. BlueGate suggests a ratio of 1:4, with 20% equity and 80% debt.

Raising equity

Phase 1 is to deal with the equity chunk, which will be $20 million in total. BlueGate and your laywers set up a new legal entity, which you name Bloks Inc. You’re going to be the lead investor, and will put in $5 million of your own money for 25% of the shares. BlueGate assures you that they are experts in ‘equity placement’, and can find a home for the remaining 75% of the shares. They have many friends at funds who can be convinced to put up the other $15 million.

After a few weeks, and a range of meetings, BlueGate’s team secures pledges for $5 million from a ‘family office’ that runs money for the super-rich, $5 million from an offshore fund, and $5 million from a local property investment fund. The $20 million equity chunk is now ready, but it will only be enough to cover the planning, permits, foundations and ground floor.

Raising debt

So, Phase 2 of the plan is to raise $80 million in debt financing. Again, BlueGate showcases their extensive ties to the super-rich and the super-big:

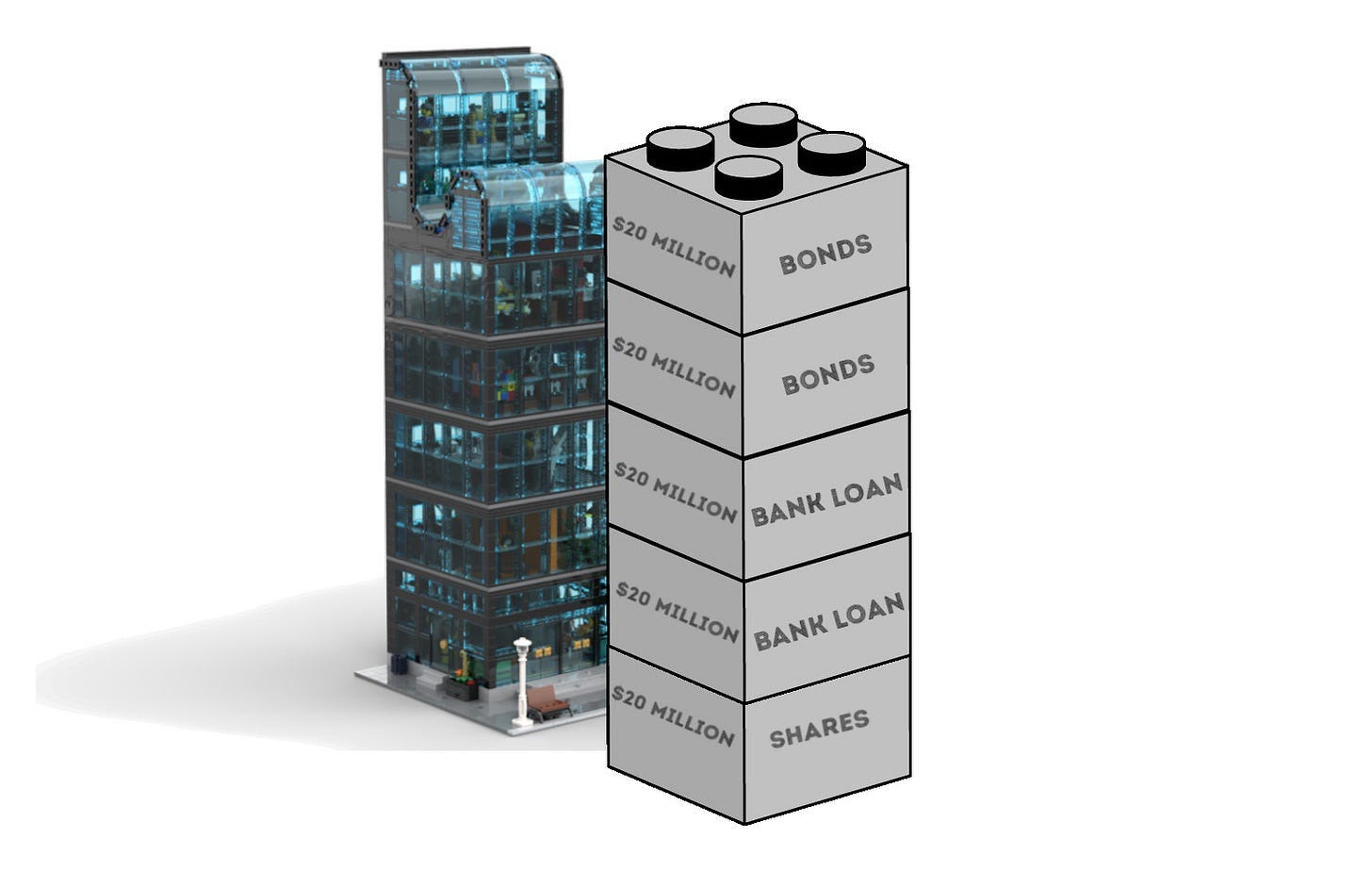

They want to create a blend of different debt investors (creditors), so their first step is to approach two commercial banks. They get each of them to grant you $20 million in credit (incidentally, this will involve those banks creating new money). This $40 million can probably scrape you another three floors…

There’s still one more normal floor and a fancy roof level to be financed, plus all the trimmings, so BlueGate now approaches a range of specialist funds and high-net-worth individuals to convince them to buy bonds. ‘Buying a bond’ is just the act of lending money in exchange for a fixed-promise-for-future-money encoded into a tradeable contract (‘bond’).

Now that both the equity and debt financing is in place, let’s zoom out and see our Bloks Inc. corporate circuit in action. Imagine the money from the creditors (debt investors) and shareholders (equity investors) charging Bloks up like a battery. That money is then blasted out to mobilize a small army of contractors, suppliers and construction workers who will make the building emerge out of the ground as the money runs down.

As the workers leave, you’re left with part ownership of a completed building, alongside a bunch of other financiers who also want a cut. To realize that cut, however, you need to make a profit, but where’s that going to come from? You need a customer…

You consider trying to manage the property yourself, finding renters who will pay. In this case your customers would be startups buying access to the building. Alternatively, you can just try flip the building by selling the whole thing to some much bigger property holder. You decide to go with this latter strategy, and BlueGate even has a bespoke service to help you find a buyer for the thing they helped finance. They introduce you to a major real estate investment trust (REIT), that has a pre-existing portfolio of buildings that they own and rent out.

From the perspective of this REIT, Blok Inc. appears in their world as a new potential supplier trying to flog them a new asset to add to their existing portfolio. The REIT boss instructs his analyst workers to do an assessment of your building…

The sale

Let’s assume that the REIT decides to buy the building. This is where leverage can get fun. If the rental market is solid, the analysts might suggest a price of $120 million for the building. From the combined perpective of the equity and debt investors in your project, that’s a 20% profit relative to how much the building cost to build. Nevertheless, given that the debt investors’ cut is absolute - it stays fixed - none of that relative increase goes to them. The entire increase accrues to the equity investors, which means - relative to their opening stake - their money just doubled from $20 million to $40 million (with your personal stake going from $5 to $10 million). That’s leverage for you. It’s sometimes called ‘gearing’, because just like a gear might amplify the affect of a foot pressing down on a bicycle pedal, leverage transmits an amplified positive return to the equity stake. Here’s a simplified representation (it’s simplified because the amounts shown don’t account for interest owed to debt investors, but let’s just ignore that):

Unfortunately for you, gearing works both ways. If, for example, the building gets completed just as a global pandemic hits and demand for office space plummets among tech startup workers, the analyst valuation of the building might crash to $90 million. This hits the equity investors first. In this case, a 10% loss relative to building costs crushes the equity by 50%. You get an amplified version of the loss. The debt investors take their absolute share and leave. BlueGate mourns your loss, after which they take their advisory fee - which might significantly eat into that remaining slice you have - and leave.

Calling all lecturers and professors: Next week I have the pleasure of presenting my Lego models to students at Stony Brook University in New York. If you’d like me to talk to your students, drop me a line!

Playing the Advanced Finance Game

What I’ve shown above is pretty basic finance, and there are two things to say about basic finance. Firstly, it’s built upon a much deeper and richer foundational layer of ecological systems, human beings, politics and - eventually - monetary systems, all of which I cover in my Intro to Economic Life course.

Secondly, basic finance can be massively complexified. There are many exciting, and increasingly dodgy, things you can do to play a more advanced finance game, such as:

Offshore finance: build complex legal structures, like a shell company that owns a shell company that lends to a shell company that is also owned by you, so that it can buy the shares

Financial engineering: create new and weird combos and hybrids of debt and equity (e.g. Silicon Valley thrives on ‘convertible notes’, debt instruments with inbuilt options that can convert them to equity)

Finance your financing: In our original scenario above, you were required to put in $5 million, but you could borrow $4.5 million of that from another bank (or other debt investors), which means you could put in $500k to get a 25% equity stake, which means you’re now leveraging your leverage! (something that hedge funds are notorious for doing)

Securitization: the original banks involved might take their stakes and place them in a new offshore vehicle, alongside 1000 other loan contracts they’ve harvested, after which they can ‘tranche’ that package into different equity and debt slices that can be sold off. Now the combined interest that accrues to the pool of loan contracts can get refracted out like a monetary rainbow to a whole range of new investors, some of whom might insanely leveraged

Derivatives: you might make bets on the side to protect yourself against changes in the average price of properties (e.g. property index derivatives), while the banks might be using interest rate derivatives to manage various aspects of their exposure. Perhaps your bond-holders might pay away some of their interest into a credit default swap (CDS) offered by an investment bank, in exchange for compensation in the event of your bankruptcy

Mix it all up! Perhaps that investment bank can take the other side of that credit default swap, and place it - alongside other CDS contracts - into a new offshore vehicle. Now they can sell the tranches of that new SYNTHETIC CDO! This is highly recommended if you wish to trigger a global financial crisis.

$$$

“History Doesn't Repeat Itself, but It Often Rhymes”

~ Mark Twain ~

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

"Pessimism of the Intellect, but Optimism of the Will"

“Educate yourselves because we will need all your intelligence.

Be excited because we will need all your enthusiasm.

Organize because we will need all your strength."

~ Antonio Gramsci ~

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

"Spanish Moon"

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

:))....What I'm Reading...:))

1. Jonathan M. Katz, "GANGSTERS OF CAPITALISM: Smedly Butler, The Marines, and The Making and Breaking of America's Empire", 2021.

Greg Grandion, “Empire’s Workshop: Lain America, The United States, and The Rise of The New Imperialism”, 2010.

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

:))..."Back To The Future"...:))

~ Progressive Political Economy ~

~ A Pedestrian's Guide ~

http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~rbutler/shortcourse10.htm

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

"It Ain't Over Till It's Over."

~Yogi ~

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

Thanks for reading $ Financial Butler $

~ Subscribe it’s :))..‘FREE’..:)) ~